Heritage Health

01 Jun 2019

Long Read

What has kept India’s heritage structures standing tall? And what are the challenges in conserving them? CW has some answers.

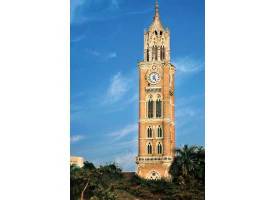

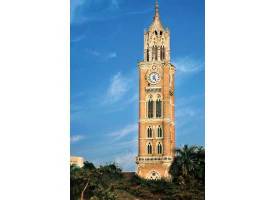

Victorian Gothic architecture in the 19th century was reflected in the architecture of British colonies overseas, including the Old Fort of Bombay where buildings were designed by leading British architects.

“The need to reflect the power of the state in the built form was important for the British throne,” says Brinda Somaya, Principal Architect, Somaya and Kalappa Consultants. Interestingly, these structures were built with local, natural and sustainable materials, and have withstood the test of time.

Past perfect

Speaking of quality, A Vijaya, Director Programme, Architectural Heritage Division, Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH), says, “All our traditional buildings are superior, not just the ones from the British era.

Those are load-bearing masonry structures in long-lasting, locally available materials such as stone, timber and lime mortar, which are not used anymore.”

And Conservation Architect

Vikas Dilawari affirms, “The craftsmen took pride in their work and went beyond the call of duty to ensure the best workmanship.”

He sees a substantial change in the environment today. “Commercial gains have taken precedence over other factors and have become the most important component. We do not have the skilled craftsmen who have good experience and knowledge about their materials.”

Present imperfect?

Undoubtedly, the life of well-built stone buildings is naturally longer than the cement-based construction used in the rapid production of today’s buildings.

“The materials used in the British era were more durable compared to the materials used today, where we moved from stone structures to buildings with steel and concrete,” says Somaya. Many colonial buildings built by the British were institutional ones, which were a statement and meant to be imposing as well as awe-inspiring to the local population.

“Comparing such structures, where additional attention was paid to their construction with the goal of lasting many lifetimes, with residential buildings is totally not right, although it is true that construction in general was also much better during the Raj.”

For her part, Vijaya refrains from comparing new-age contractors to the British, owing to the completely different times. While Lord William Bentick in 1835 tried to auction the marble of Taj Mahal and ship it away to England, the remains of Amaravati Stupa were actually shipped; there was also Alexander Cunningham who founded the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1861, John Marshall, the Director General of ASI from 1902 to 1928 oversaw the excavation of Harappa and Mohenjodaro and many others.

“By the 19th century, the British had already established conservation philosophies and institutions in their country, which helped them practice the same in India, with help from Indian craftsmen,” she says.

“Pre-Independence projects were mostly competition-based and, hence, the best talent usually engaged with the project,” comments Dilawari. He adds that PWD was the project-executing agency and had some fine engineers, sub-engineers and supervisors. Comparing this to present day, he says, “Standards have declined owing to several reasons. To get the job, contractors quote the lowest factor (ie L1) and the compromise starts from there.”

Skill training: The 19th century scenario

Skill is a big deficiency today. But was it available in the 19th century?

“Back then, art and the articulation of structures at the time of construction were carried out manually; therefore, these skills were inherited from earlier generations and passed down with great attention to detail,” responds Somaya. She adds that after the Industrial Revolution, technology offered mass production in less time and with less effort. The material palette changed to steel, RCC and glass, which reduced the need for traditional skills in building construction, resulting in a decline of skilled workmen.

About training, Vijaya examines the prevalent practice. “In the 19th century, the apprenticeship was much in practice in every field,”

she says. “Traditional building knowledge and craft skills were also transferred from older to new generations, which does not hold good anymore.”

Dilawari expresses his surprise over how PWD handbooks were meticulously updated and recorded details of traditional lime surkhi mortar, which saw the usage of jaggery water and other traditional ingredients. “Now, things have changed and the focus is more on faster, economical, and ready-to-use lookalike things,” he says.

Challenges in maintenance and retrofitting

Today, there are 3,686 monuments protected by ASI, 7,000-odd structures protected by state archaeology departments, and at least half-a-million buildings under PWD, Railways, universities, schools, postal departments, hospitals, cantonments and other government departments.

Apart from world heritage sites and a few important monuments, ASI does not have a good record for maintenance of monuments.

The same holds true for the state Archaeology departments and PWDs. “CPWD has removed traditional building practices and items from the schedule of rates (SOR) and the engineers are not equipped with traditional repair knowledge anymore,” adds Vijaya. Also, repair with modern materials and techniques damage our traditional buildings further.

Evidently, responding to heritage in a sensitive way is important.

That said, Somaya points to “technical, organisational and financial challenges.” One major technical challenge is carrying out retrofitting and maintenance works without appointing expert professionals well-versed in the field of conservation. “Poor financial support and the rising cost of materials and technologies have become major issues too,” she adds. While introducing adaptive reuse in heritage buildings for contemporary functions, one needs to incorporate modern technologies such as HVAC systems, fire-fighting, security and lighting, which are challenges of a different sort.

Dilawari, too, foresees several challenges in the field as it is a newly emerging discipline.

“The government has introduced heritage legislations for maintaining significant heritage buildings but has not given any encouragement vis-a-vis law or financial support for its repairs,” he says. As a result, conservation does not find a strong case to survive and redevelopment or reconstruction takes over. In his view, for conservation, the person or agency should have a good philosophical understanding of heritage and history as these require special skill sets depending upon the age, condition, materials, etc, of the structure. Traditional materials are not IS products – lime, for example – and, therefore, they are not easily available sometimes. Also, the traditional skills for handling these have vanished or are discontinued and need to

be revived.

Vijaya believes that the biggest challenge or threat is ignorance and apathy towards heritage buildings. And then, of course,

is allocation of funds for repair and maintenance. “We do not follow the saying, ‘A stitch in time saves nine’,” she rues. “We vandalise and wait for them to fall.”

Related Stories